DIS2 featured in CORDIS Results in Brief

Read more here:

Read more here:

I was interviewed about my research on disability during the 1918 flu and its relevance for today. Read “How vulnerable groups were left behind in pandemic response” by Richard Gray here:

https://horizon-magazine.eu/article/how-vulnerable-groups-were-left-behind-pandemic-response.html

Last week, I presented my project on disability as a risk factor during the 1918 pandemic for the webinar series of the Centre for Research on Pandemics & Society. Watch the video here:

I noted several sources that helped determine disease values used in the simulation model (and similar models for Newfoundland communities – see work by my PhD supervisor, Lisa Sattenspiel, and our colleagues). These sources include:

“‘An Avalanche of Unexpected Sickness’: Institutions and Disease in 1918 and Today.” Chelsea Chamberlain. June 23, 2020. Society for Historians of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. https://www.shgape.org/an-avalanche-of-unexpected-sickness/

Ferguson, N. M., Fraser, C., Donnelly, C. A., Ghani, A. C., & Anderson, R. M. (2004). Public health risk from the avian H5N1 influenza epidemic. Science, 304(5673), 968–969. https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.1096898

Mills, C. E., Robins, J. M., & Lipsitch, M. (2004). Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza. Nature, 432, 904–906. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03063

Almost two years after I last sat down with Hallvard Lavoll and the Viten og snakkis podcast, we met again to talk about my project. Take a listen here: https://vitenogsnakkis.oslomet.no/2021/05/14/researching-a-pandemic-during-a-pandemic/

COVID-19 has shown that people with disabilities are at increased risk of severe illness and death during pandemics. Interacting biological and social factors likely contribute to these differences. For example, risks are especially high for those living in institutions.

Yet, few researchers have studied the experiences and outcomes of disabled people during past pandemics, including the 1918 influenza pandemic. As part of the webinar series of the Centre for Research on Pandemics & Society at Oslo Metropolitan University, Jessica Dimka, Ph.D., will present the main results of her Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowship in her talk, “Disability, Institutionalization, and the 1918 Flu Pandemic: From Historical Records to Simulation Models.”

Key points of the talk include:

The talk will conclude with a discussion of the relevance of this work for COVID-19 and future pandemics, including areas of future research, policy implications, and the disabling effects of pandemics.

For a Zoom link, please contact jessicad@oslomet.no or masv@oslomet.no

The talk will be in English, and International Sign interpretation is arranged. For general questions about the webinar including accessibility concerns, please contact jessicad@oslomet.no or ninha@oslomet.no

It’s fair to say that this year has not been what I was expecting or hoping for, and I’m sure that is true for most people. However, I am grateful that my family has remained healthy and that I have been able to work safely from home.

Some of my plans and timelines for this project have changed, of course. But I also have had the opportunity to co-author several articles, now in various stages of review, connecting historical pandemics to COVID-19 and addressing issues of inequality and preparedness. I am excited to share those when they are ready.

Meanwhile, I’ve been working on making sense of historical records from Sweden. My preliminary analyses suggest there were differences in 1918 flu mortality outcomes between people with and without recorded disabilities, but these are clearer to spot when considering people noted to be in institutions vs. the whole population. While I have remaining analyses to do, these findings reinforce the importance of the physical environment and social attitudes in pandemic outcomes when it comes to disabled people.

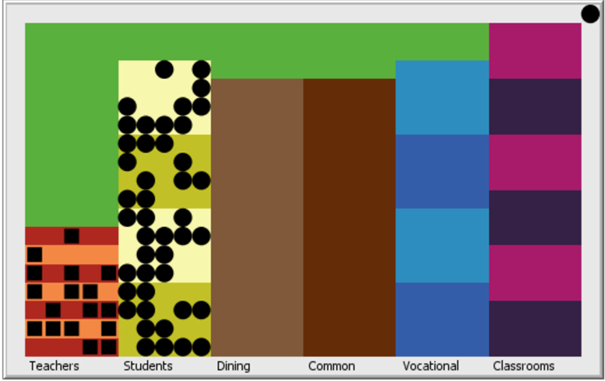

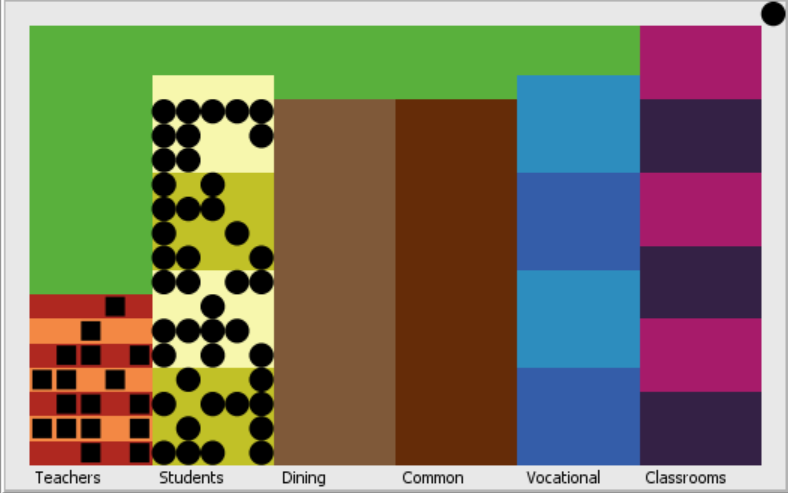

I also have drafted the complete model code for my agent-based model. The image below is the appearance of the “world” at the start of a simulation, depicting staff and students in a school for children with disabilities. The schedule of activities and other details are based on archival material for a number of such schools in early 20th century Norway, especially Holmestrand School for the Deaf. The code needs to be carefully tested first, but hopefully soon I will be able to start analyses. Ideally, this model will not only improve our understanding of how diseases spread within institutions but also be a tool for testing how well potential interventions might work.

Image description: Map of the model school. Social spaces appear as rectangles of different colors, and they include boarding rooms for staff and students, the dining room, a common room, vocational classrooms and teaching classrooms, as well as external grounds. At the start of a model run, staff (squares) and students (circles) are in their bedrooms, most of which are shared. One student is in the upper right corner, reflecting the fact that usually a small number of students lived or boarded outside of the schools.

Image description: An external view of Holmestrand School for the Deaf, showing a large building with a smaller extension and fenced grounds covered in snow. Date unknown, although the picture is sepia-tinted and the folder at the archives contained material from 1899-1943. Held at the National Archives of Norway (RA/S-1021/F/Fh/Fhp/L0061 – Holmestrand off. skole for døve).

I am definitely looking forward to the next stages of this project, and I hope everyone has a much better new year than the last one!

I am happy to share the first paper of the DIS2 project, recently published by the Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. The title is “1918 Influenza Outcomes among Institutionalized Norwegian Populations: Implications for Disability-Inclusive Pandemic Preparedness.”

In this paper, my co-author, Svenn-Erik Mamelund, and I describe previous studies that found connections between disability and the flu. We also discuss how many countries do not consider disability enough in their current plans for dealing with pandemics like COVID-19.

We looked at Norwegian institutions during the 1918 flu pandemic, including schools for children with disabilities and psychiatric hospitals. Reports by school directors showed that the children were more affected while the staff seemed to be mostly fine. At the hospitals, staff members were the first to get infected, and a larger percent of them got sick. But a larger percent of the patients who did get sick died.

We end with suggestions for how pandemic plans today can better include disability. Our suggestions include:

Read the full article here: http://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.725

This paper is particularly timely due to the current COVID-19 situation. For just one example of how organizations run by people with disabilities and their families are responding, check out the resources provided by the European Disability Forum: http://edf-feph.org/covid19

As someone who has spent much of the past decade or so thinking about historical pandemics, it is quite surreal to be in the middle of one. On one hand, it is rewarding to be reminded that what I’m working on is important and relevant today, and I have identified many new questions to study in the future. On the other hand, that’s not much of a silver lining when there’s so much uncertainty and worry. Like many other people, I’m concerned for myself, my family and friends, my community, and indeed people around the world. While the MSCA fellowship is an amazing opportunity, it also means I’m an ocean away from the people I love the most.

With cancellations and social distancing and everything else, I have had to rearrange and prioritize activities in my project. I also am trying to help out where I can. For example, I will be providing content to some teachers who are now shifting to online education. I also want to help raise awareness of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with disabilities. For example, how are life or death decisions being made about who gets treatment and who is “expendable”? What happens to the people who need various medical supplies on a daily basis when there is panic buying and supply shortages? Why is working or learning from home possible now when before that was commonly written off as an unreasonable accommodation? And yet at the same time, people with disabilities are still often being excluded from public health responses and communication, economic relief packages, and accessible education.

These and many other questions are being raised and discussed by people who are much more eloquent and experienced with these matters than I am. As important as I think it is to study historical pandemics and to use the experiences of the past to inform the present and the future, I think it’s more important to listen to the voices of the people directly impacted right now. So, I want to conclude this post by linking to several Twitter accounts of people and organizations who are particularly concerned with disability during this pandemic. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but it’s a good place to start: @MyEDF, @CDSLeeds, @Imani_Barbarin, @emily_ladau, and @jaivirdi

To everyone: stay healthy and stay home, as much as you can!

As hard as it is to believe, not only is 2019 almost over, but I’ve also been here in Oslo, working on this project, for about 7 months. It seems like a good time to take stock of some of the major accomplishments and to look ahead.

Our first manuscript is under review. We hope to get feedback and see it published soon.

I presented at three international conferences in Hungary, Iceland, and Canada, and gave several talks at smaller local and regional workshops and seminars, including at OsloMet, at NTNU in Trondheim, and for the Sociology and Human Geography department at the University of Oslo. I also was able to attend a small conference in London, celebrating the opening of the archives at the Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability.

I have obtained necessary approvals and have started collecting materials from Norwegian archives. I have (roughly!) translated many sources already, gaining insights on institutional practices and policies, as well as finding references to health conditions faced in the past.

The next steps include continuing to work through Norwegian sources, including trips to regional archives around the country. I am also traveling to Sweden soon, where colleagues at Umeå University are graciously assisting me with data collection from their population databases. These analyses will be the foundation of another manuscript. I will also present in March at another conference in the Netherlands.

This list highlights just some of the many exciting things from the last several months and the months to come. For now, though, god jul og godt nytt år!

Disability researchers and activists often emphasize the importance of the social model of disability and similar perspectives. This model recognizes the role of barriers, including social attitudes, that contribute to the disablement process. A person might encounter more or fewer barriers in different contexts or over time.

In my project, I also apply the concept of syndemics, which shares similar themes with the social model of disability. A syndemic is characterized by two or more interacting health conditions that are influenced or worsened by social inequalities and environments.

Because my project considers a historical epidemic, I must also think about how attitudes about and understanding of both disability and infectious disease have developed over time. Two important considerations around the time of the 1918 flu are the eugenics movement and World War I.

In this picture, I am describing these considerations during a recent talk at OsloMet for people interested in Norwegian demography. We discussed whether it is appropriate or even possible to separate the “biological” and “social” factors that might produce health disparities for people with disabilities, and how historical analyses can be applied to present-day concerns. These questions are important and I welcome your own thoughts on them!