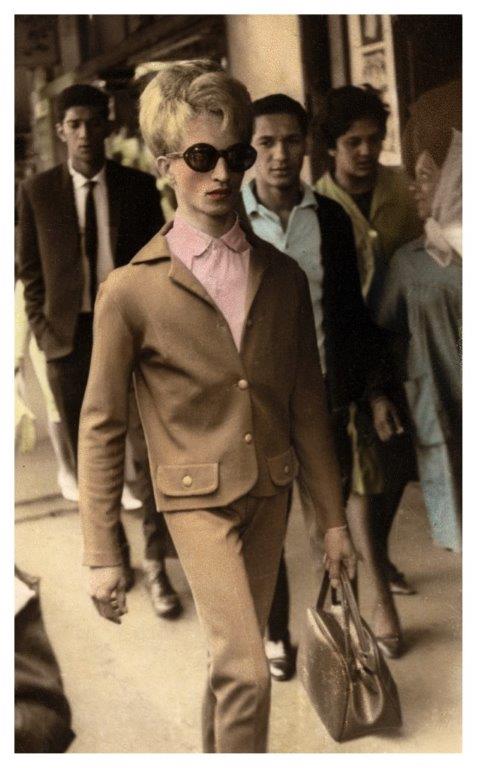

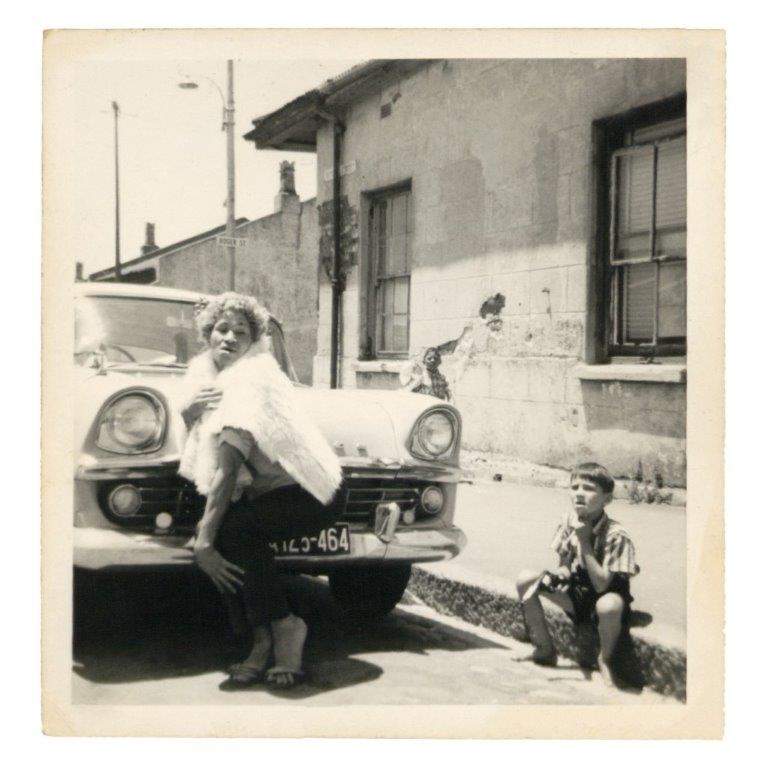

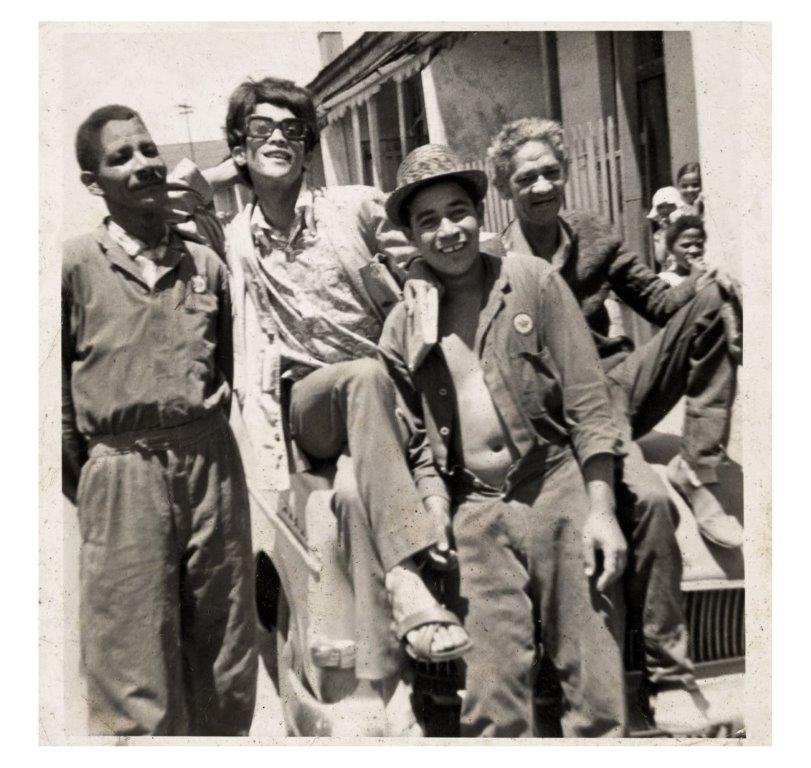

The streets of District Six were busy and full of people who knew each other. It was a place where identities were shaped by street culture. The streets of District Six evolved into spaces for performance, peopled by a ready-made audience of pedestrians. Kewpie and friends, embodying their film star personas, embraced the possibilities for performance on the streets of their neighbourhood, publicly inscribing their identities. Skilled and practiced in front of the camera, they would strike expressive, playful and provocative poses. These street scene photographs demonstrate the extent of integration of queer people into the broader District Six community, as well as the confidence that Kewpie and her friends had to be themselves. Despite this level of visibility, some queer people were still the targets of discrimination and violent harassment.

“I was on my way to work in the morning at Salon Kewpie in Kensington”. – Kewpie

Darling Street c. 1967

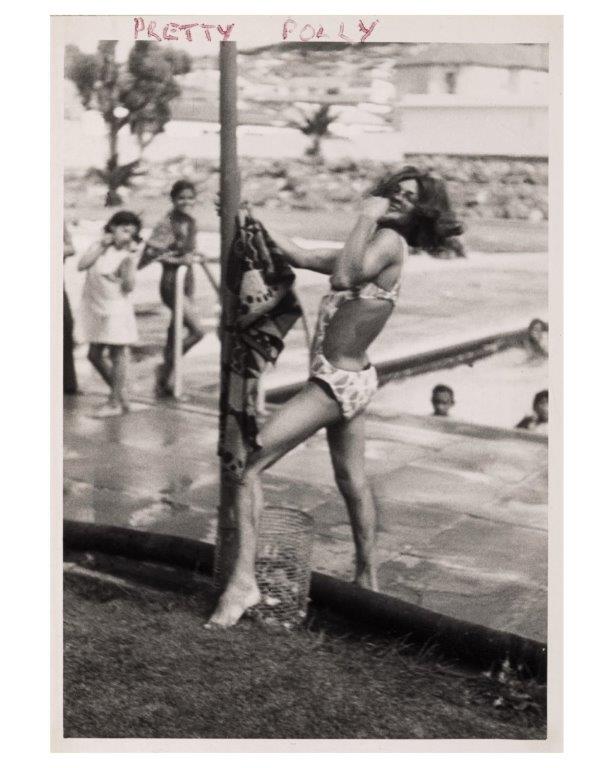

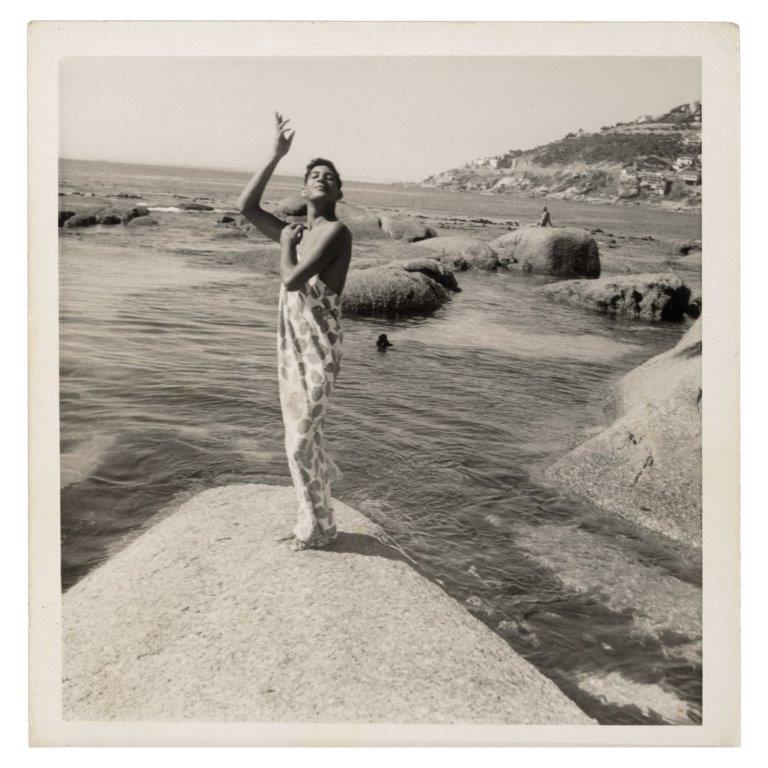

Kewpie and her friends were by no means confined to District Six. As well as working in Kensington and performing in shows all over the peninsula, Kewpie would regularly visit beaches, parks and swimming pools for days out.

The 1950s to the 1960s was a period of increasing oppression for queer people as the Apartheid government began to police sexual behaviour across South Africa. During the 1960s the government attempted to pass legislation that would have made male and female homosexuality an offence punishable by a prison sentence. A political campaign meant the resultant 1969 amendment to the Immorality Act was less draconian than feared, but it still criminalised gay sex.

Significantly, Kewpie and her friends regularly wore bikinis in a range of public spaces: at the beach, at the swimming baths, and in the park. Exposing their bodies so openly in public was highly subversive, and contravened anti-masquerading laws, constituting actions that were punishable by a prison sentence.

The election of the National Party (the Apartheid government in South Africa) in 1948 accelerated the already well-established process of racial segregation in Cape Town. Following the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953, all public amenities were segregated along racial lines, including parks, buses, and hospitals. Beaches were strictly segregated, with those considered the best reserved for ‘whites only’.

Despite numerous pieces of legislation designed to segregate the city, «grey areas» remained and Capetonians, including Kewpie, continued to move around the city as they went about their business. Photographs in the collection show Kewpie and friends at Fourth Beach, which was designated a ‘coloured’ beach, but gay men of all races would often meet here. The District Six hairdressers retained and even gained white clients during this period, but they would do their hair upstairs, out of sight.

Rutger Street

Sir Lowry Road

Strandfontein

Trafalgar Baths

Fourth Beach

Kewpie and her friends were by no means confined to District Six. As well as working in Kensington and performing in shows all over the peninsula, Kewpie would regularly visit beaches, parks and swimming pools for days out. The 1950s to the 1960s was a period of increasing oppression for queer people as the Apartheid government began to police sexual behaviour across South Africa. During the 1960s the government attempted to pass legislation that would have made male and female homosexuality an offence punishable by a prison sentence. A political campaign meant the resultant 1969 amendment to the Immorality Act was less draconian than feared, but it still criminalised gay sex.