Marta Bivand Erdal and Lubomiła Korzeniewska write about the challenges of conducting interviews in various languages.

By Marta Bivand Erdal and Lubomiła Korzeniewska

As we interview migrant nurses from the Philippines and Poland living in Norway, we reflect on the role language plays in our research. Both of us speak Polish, English, and Norwegian. These abilities position us in particular ways linguistically vis-á-vis the nurses we interview.

Does it make a difference to be interviewed in your mother tongue, or not? Is it different than talking to researchers in your second or third language? Does it matter that you and the interviewer share several languages? And what can we, the researchers, do in order to not get lost in translation, but stay true to what our interviewees tell us? As we conduct interviews, we keep in mind the old adage: “It is important not only what people say, but also how they say it.”

Juggling multiple languages is normal for migrant nurses

In our dataset, only a few interviews are not multilingual. Our respondents juggle several languages on a daily basis, depending on the linguistic competencies of their patients and colleagues. They read medical literature in multiple languages and use different languages in their free time. When encouraged to use the language(s) they felt most comfortable with, Filipino participants would switch back and forth from English to Norwegian. Although neither English nor Norwegian were the mother tongue of the interviewees or Lubomiła, the interviewer of the cohort we write about, these languages were crucial in collecting data:

“So, I got [my application] rejected around 2013. And they sent me to school, and I was, like, okay, I will not go there. I am not going back to zero, and study nursing again. That’s too much, I mean, like, too much stress and everything, to study (…) å studere på nytt selv om jeg er jo sykepleier, ikke sant? [to study again, although I am a nurse, right?]”

(Bernadette[i], a Filipino nurse)

Polish participants also used Norwegian words in interviews conducted predominantly in Polish, the native language of both the interviewers and the interviewees. Since English is the language of the WELLMIG research project, we translated interviews conducted in Polish into English. In these translations, we maintained Norwegian terminology whenever it was used. Similarly, we preserved Polish idiomatic expressions, especially when the English equivalent was less than perfect:

“So, well. At that time, I was already working as a volunteer [nurse], so (…). Even if I skipped some parts, I had something [some hours] as a volunteer [nurse]. So, I kombinowałem jak mogłem [I hustled as much as I could] …”

(Rafał, a Polish nurse)

The possibilities and limits of transcription

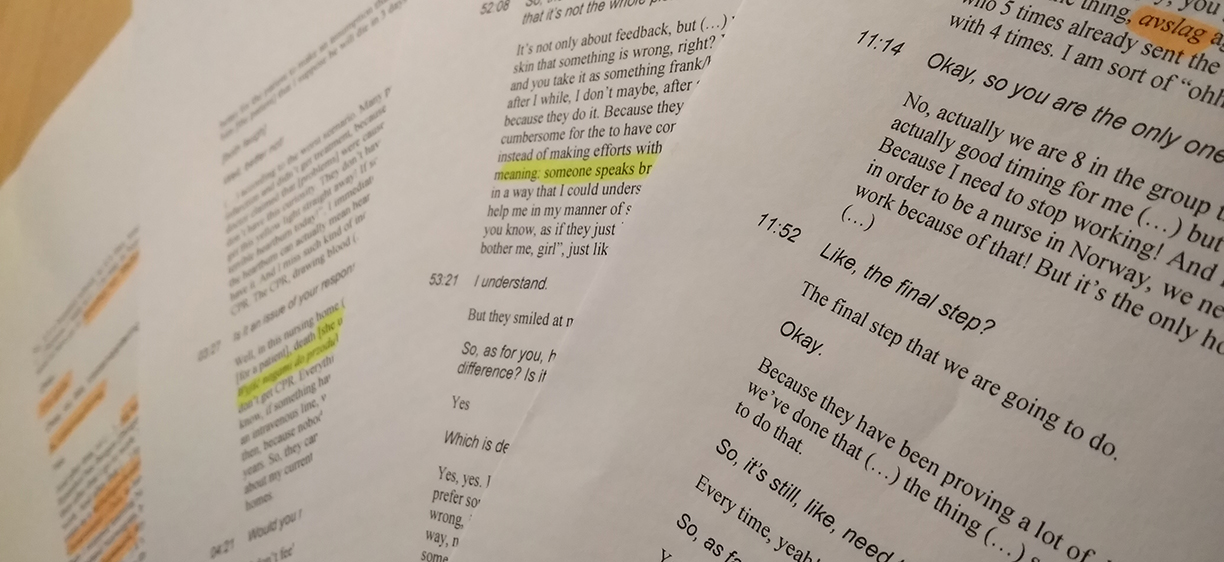

After Lubomiła completed the interviews, we started analysing the data and writing academic articles. But when interviews are carried out in multiple languages, citing them requires additional decision-making and quality control. The challenges we face relate to how we can reproduce multilingual quotes without losing the linguistic nuances. This has concrete implications for how we work with interview transcriptions in order to change a spoken word into a written one.

We could cite multilingual quotes without translations, but most journals are published in one language only. An alternative would be to make necessary translations and add them in footnotes. Another would be to interrupt the flow of the quote in text with brackets, as we have shown in the above examples. There is no simple answer to the question of how an accurate representation of the spoken word ought to look.

The role of language is an important and well-established methodological issue. In our case, when both the researcher and the interviewees might be utilizing a second or third language, intonation and pauses cannot be the focus of textual analysis of interview transcripts. Yet, transcriptions form the basis of much of our analysis. Transcriptions reflecting significant language-switching put the transcription format to the test even more. This, in turn, challenges the often taken-for-granted ways of representing the spoken word in academic literature. Furthermore, it calls for transparency of the research process, including a need to detail the translation of quotes.

Reflecting on the multilingual research process

As many international collaborative research teams, the WELLMIG team switches languages constantly, both in the interview process and in communicating with each other. Multilingual research practice creates opportunities for questioning what might otherwise not be questioned. It also reflects the multilingual life-worlds of research participants in the context of international migration.

Allowing research participants to freely switch languages corresponds well with their everyday experiences and quite possibly allows them to better express themselves. Our experience suggests that benefiting from multiple language competencies – and reflecting on the various implications of the multilingual research process – helps us to avoid getting lost in translation.

[i] Names used are pseudonyms.