The New Year is a time for taking stock, reflecting, and looking ahead. The researchers in the WELLMIG team took stock of our readings in 2020.

Marie Louise Seeberg

Thankful that I am an avid reader, I look back and realize how books have helped me through 2020. Here are some of the ones that have transported me to other times and places during this year of being utterly stuck:

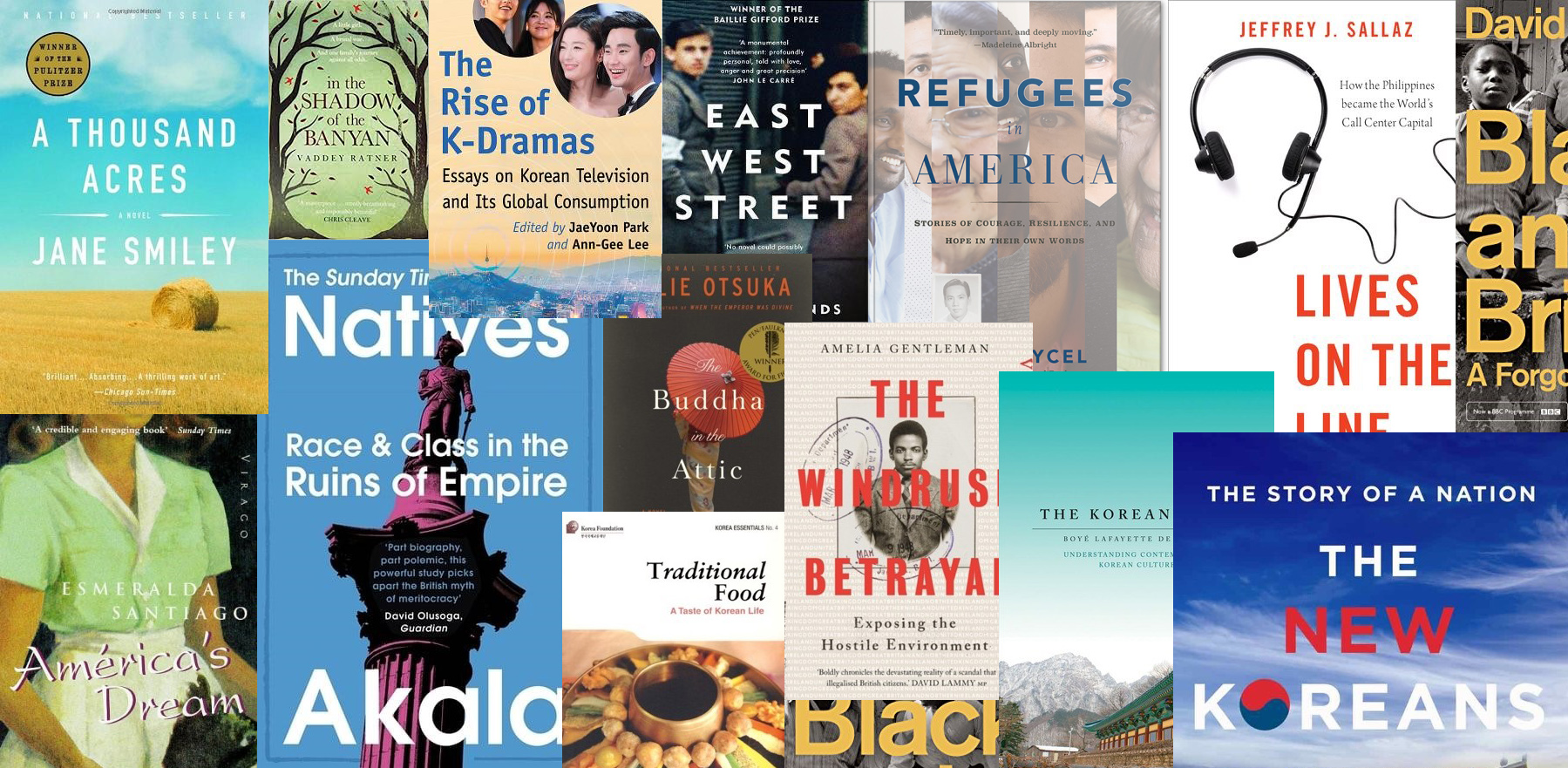

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (goodreads.com) by Ocean Vuong. This is the first novel by the poet, and it is, as I had expected, very well written. It is a coming-of-age kind of book, in the form of a long letter from a young Vietnamese American man to his mother, where he tries to explain to her (and to himself) who he is and why he is the way he is. It is also a love story between two young men, and this story is intertwined with the story of his mother’s life as a Vietnamese woman, the American/Vietnam war, and the refugee experience, along with her personal story of violence and grief.

Confession with Blue Horses (goodreads.com) by Sophie Hardach is in some ways a similar story, although the setting and the tone are completely different. Here, too, we have a young person trying to understand their refugee mother- her loss and life changing decisions, while striving to come to terms with their own identity and background. In this book, we are transported to London and to the German Democratic Republic, partly in the 1980s and partly in contemporary times. There is a mystery, too: what happened to the protagonist’s brother when the rest of the family escaped to the West? The refugee experience (to the extent that it may be generalised as “an” experience) sets the tone for this book as well, while we also learn a good deal about everyday life back in the DDR.

With The Buddha in the Attic (goodreads.com) by Julie Otsuka we find ourselves following young Japanese mail-order brides on their way to their new husbands and lives in America in the 1930s. Their romanticising dreams and hopes are quickly turned into more realistic experiences of hard work and everyday aspirations as they settle into their married lives. Most of the families are hired as farm hands, and we follow them in the first-person plural, not following one woman or family in particular, but rather their collective experiences. These culminate in the internment of Japanese Americans during the second World War. Again, I learned a good deal about everyday lives not paid much attention in history books.

East West Street: On the Origins of ‘Genocide’ and ‘Crimes Against Humanity’ (goodreads.com) by Philippe Sands is not fiction, but unravels the story of origin of these two key concepts in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Although not directly about migration as such, it examines the historical, geographical, and individual contexts of these two terms that, each in their way, try to grasp the unspeakable acts of evil that have forced millions to become refugees, not only from the Third Reich of Hitler, but from other regions of the world up to the present moment. It is a complex book, weaving together the lives of the two main ‘authors’ of each concept, with the life of the author, Philippe Sands, himself and with the history and fate of a town that has seen states come and go, its name sometimes Lemberg, sometimes Lwow, Lvov, or Lviv. Exceedingly well written, this learned tome reads almost like a detective story, and I would read it again any day.

Still, for me the winner of 2020 (if this is a competition) has to be In the Shadow of the Banyan (www.goodreads.com) by Vaddey Ratner. This book really got under my skin. It tells the story of the Cambodian revolution, when the Khmer Rouge took power, through the eyes of a young child. It is a deeply haunting and poetic read, an accomplishment that becomes even more striking when you realize that the child protagonist is, in fact, the author herself. It is a fictionalised yet true story of the most extreme violence and hardship, written almost like magical realism and intimately appealing to all the senses.

Jørgen Carling

My reading in 2020 has been quite fragmented. Perhaps more than usual. I do almost all my reading in Kindle on my iPad or phone, which makes it all too easy to dip in and out of different books. Moreover, the coronavirus has taken its toll on my concentration span in the second half of the year, meaning that I have read in a lot of books, though there are few that I have read cover to cover.

One exception is Lives on the Line (global.oup.com) by Jeffrey Sallaz, a labour sociologist. The book’s subtitle is ‘How the Philippines became the World’s Call Center Capital,’ but it is mostly about the life worlds of call centre workers. After having done ethnographic fieldwork in a ‘depressing little call centre in my struggling American city,’ as he describes it, Sallaz followed the international outsourcing to Manila where he carried out the research that led him to write Lives on the Line.

What is interesting from a migration perspective is how call centre work, according to Sallaz, represents a ‘middle path’ between entering the local labour market and going abroad. Call centre jobs pay much less than even unskilled work abroad, but offers a relatively quick route to stable income compared to other career options for college graduates in Manila. This also means being able to move out from one’s parents’ home, yet not being isolated from family as an overseas worker.

As a migration researcher, I often find it rewarding to read books that are not primarily ‘about’ migration but describe a social context where migration plays a role. Lives on the Line is a prime example of such a book.

Izabella Main

I spent the 2019/2020 academic year in the United States as a Fulbright scholar. In addition to conducting research and giving guest lectures at various universities in Washington, DC, I also set out to read American novels, as a way to learn more about Americans, their culture, and way of life. This plan of mine was a fun, relaxing, and inspirational way to explore new ideas.

In high school, I read Polish translations of the classics – Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Harper Lee, Henry James, J. D. Salinger, John Updike, Jack Kerouac. The first novels I read in English included Beloved, Song of Solomon, and Love by Toni Morrison. I was also fascinated by Jamaica Kincaid, an Antiguan-American novelist, especially her novel Lucy.

In 2020, the first book I chose to read was Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming (becomingmichelleobama.com), describing her childhood in Chicago, her first professional experiences, motherhood, her relationship with her husband, Barack Obama, and the challenges her family faced during the presidential campaign and while living in the White House. The memoir is deeply personal, emotional, and honest, but also warm, funny, and entertaining. Michelle is a true role model for women and men in diverse circumstances. A great story.

The next book I picked up was the novel A Thousand Acres (goodreads.com) by Jane Smiley. It is a story based on William Shakespeare’s King Lear and it received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1992. It was also adapted to the silver screen as a star-studded film, staring Jessica Lange, Michelle Pfeiffer, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Jason Robards, and Colin Firth. Aging Larry Cook announces his intention to incorporate his 1,000-acre farm in Iowa, handing complete and joint ownership to his three daughters, Caroline, Ginny, and Rose. When the youngest daughter objects, Larry takes her out of the deal. This sets off a chain of events that brings dark truths to light and explodes long-suppressed emotions. A reader gradually learns about family secrets and harsh life on a family farm: long-term sexual abuse of the two eldest daughters, abusive husbands, lies, and even murders.

The next novel transported me from Iowa to Ohio, another midwestern state. The Abundance (goodreads.com) is a novel by Amit Majmudar, a son of Indian immigrants who grew up near Cleveland. It is a story about Mala. When Mala learns that her mother has only a few months to live, she decides to learn everything she can about her mother’s cooking. Her brother, Ronak, follows her but wants to sell their experience as a book and documentary. Their children are challenging both the Indian and American worlds. The book taught me a lot about cultural divides and intergenerational conflicts in immigrant families.

In Refugees in America (refugeesinamerica.com), Lee T.Bycel presents stories of individuals born in different countries. The protagonists included range from a 93-year-old Polish grandmother, who came to the United States after surviving the Holocaust, to a young undocumented immigrant from El Salvador. Some have found it easy to reinvent themselves in the United States, while others have struggled to adjust to America, with its new culture, language, prejudices, and norms. I found the story of Asinja Badeel especially touching. Asinja is a Yazidi woman from Iraq who fled the genocide against Yazidis and now lives in Houston, Texas. She wants to contribute to her new country, support vulnerable individuals, and teach about the Yazidis and their history and suffering.

America’s Dream (publishersweekly.com) by Esmeralda Santiago is a story about América Gonzalez, a woman from Puerto Rico. She works as a hotel housekeeper, cleaning up after wealthy foreigners who do not look her in the eye. América faces all sorts of family problems, both in her immediate and extended families. When she gets a chance to work as a live-in housekeeper and nanny for a family in New York City, América takes it as a sign to escape her troubles and start a new life. Her new life brings new joys, yet also unexpected events. The novel exemplifies immigrant life and explores how she realizes the proverbial American dream.

These books showed me the diversity of American life, exemplified in the characters who closely resemble my friends and neighbors in Poland, as well as those who seem vastly different. The readings also challenged my naïve ideas about the land of opportunity and counterbalanced them with hard work, challenges, and inequalities faced by immigrants. Finally, I read and learnt about cultural diversity nurtured in families and neighborhoods of New York and Midwestern states.

Marta B. Erdal

I warmly recommend reading these four books to anyone interested in human dignity, social justice, and historical perspectives on the present.

‘How to Argue with a Racist: History, Science, Race and Reality’ (weidenfeldandnicolson.co.uk) (2020) is an in-depth tour of the most up-to-date human genomics, including an incisive and appropriately critical engagement with the history of the scientific study of race, and a thorough engagement with history in general. The author’s personal family history quietly emerges, only underscoring the book’s key message: race is a social – not biological – construct.

Akala’s ‘Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire’ (newbeaconbooks.com) (2018) is a personal story and a polemic, and an extremely insightful one. It is packed with history of the British empire and its present-day ruins, yet full of nuance and humanity. Akala’s personal story, backed with massive knowledge, unpicks the reality of Black Britons from Windrush through experiences within the British educational system over the past 70 or so years. Harsh truths and realities with a clear class-dimension, and with clear differences, but also similarities to the histories of African Americans.

‘The Windrush Betrayal: Exposing the Hostile Environment’ (faber.co.uk) (2019) meticulously reports on what came to be known as the Windrush scandal. This investigative journalism is as impressive as it is chilling. Gentleman carefully unravels what happened when 83 people were wrongfully removed from the UK and 164 people were unlawfully held in immigrant detention. The stories of the people described in this book are stories of those who arrived in the UK decades ago, often as children or young people, who had their whole family, personal and professional lives firmly made in the UK, before the state tore them apart.

David Olusoga’s ‘Black and British: A Forgotten History’ (panmacmillan.com) (2017) offers a reading of British history where blacks’ and whites’ destinies – and stories – are interwoven. This is a history which traces its way back to Roman Britain, to Elizabethan times, with critical emphasis on the role of the slave trade for and in the UK, and up to present times. For anyone interested in the past – or present – of the UK, this is an essential read – not about Black Britons, but about Black British history as integral to the history of the British Isles.

While different, these books communicate a clear need for anti-racist engagement. This starts with caring to revisit our own knowledge and reflecting on the historical realities we have learnt and the perspectives therein – but also the omissions, and therefore the possible implications for our engagement with the present. As becomes clear throughout these books, however fictitious – racial hierarchies are pervasive and often implicit presences – from sports journalism, to ideas about who ‘we’ are, to how we understand historical trajectories into the present, around the world.

Elzbieta M. Gozdziak

COVID-19 brought field research to a screeching halt. Without fieldwork, the anthropologist in me felt like a fish out of water. I started looking for a substitute that would bring me closer to a foreign culture that I knew very little about. This search brought me to K-dramas and the discovery of the Hallyu wave! (korea.net) I went down a rabbit hole…

I started watching the Korean dramas the way an anthropologist studying a culture at a distance (onlinelibrary.wiley.com) would. I did not merely follow the narrative arcs of the melodramas and police procedurals, but focused also on the political and social backgrounds against which these dramas are set, as well as the everyday details of cuisine, dress, and social etiquette. I wanted to know more; therefore, I started reading books about South Korea.

Needless to say, the first book I picked up was The Rise of K-Dramas (goodreads.com), edited by JaeYoon Park and Ann-Gee Lee, professors of media communication and English, respectively, at the University of Arkansas-Fort Smith. This collection of essays focuses on the cultural impact of K-dramas and their fandoms. The contributors look at the K-dramas’ appeal to non-Asian audiences and analyze shows ranging from melodrama and romantic comedy to action, horror, sci-fi, and thrillers. They also explore an immersive fandom where devotees consume Korean food, fashion, and music to better understand their favorite shows. I had no idea about the resources the South Korean government devotes to the promotion of Korean films and television abroad- the same way the government supports export of Korean electronics.

I was also intrigued by the books on Korea and Koreans by Michael Breen. He lived in Korea for more than 30 years, working first as a journalist for The Guardian, The Times,and The Washington Times before becoming a public relations consultant in 1994 with the Seoul office of the Burson Marsteller PR agency. In 1998, Breen wrote critically acclaimed book, The Koreans: Who They Are, What They Want, Where Their Future Lies (goodreads.com). Twenty years later, urged by his agent, he wrote The New Koreans (goodreads.com). Breen talks about this book in an interview (asiasociety.org) with Matthew Fennell. As an anthropologist, I found this book fascinating, especially the apparent contradiction of moving from paddy fields into the Silicon Valley within just a few decades and the contradiction of establising themselves as a democracy, on the one hand, and being influenced by tradition and Confucian principles in their everyday behavior and social interactions, on the other hand.

I was afraid that the next book I picked, The Korean Mind (goodreads.com), would essentialize Korean culture and would not appeal to my anthropological sensibilities. I was pleasantly surprised. The late Boyé Lafayette de Mente (japantimes.co.jp) conceived of his book as an encyclopedia of the most important ‘code words’ or concepts that are fundamental to the Korean language and culture. He examined each concept in detail, discussed their evolution over the years, and provided the readers with quite the insight into the character and personality of the Korean people. Although I don’t speak Korean, the book explained a lot about the power of filial piety, the versatile bow, the intricate ways of addressing people, and many more.

I have always liked Korean food, but never attempted to cook Korean dishes myself. As I continued to watch K-dramas, where eating is so important to the narrative, I bought several cookbooks and started experimenting.

To put the recipes in context, I read the short book Traditional Food. A Taste of Korean Life (hawaii.edu) by Robert Koehler. The book is part of a series of books published by the Korean Foundation aimed at equipping international readers with basic understanding of different Korean traditions. This book explores Korea’s 5,000-year-old culinary culture and introduces the readers to the historical, cultural, nutritional, and philosophical background to the Korean rich cuisine. I liked it so much that I decided to also read Hanbok. Timeless Fashion Tradition (princeton.edu).

I am looking forward to the pandemic being over to go and travel in Korea.