On the implicit policy of the term “belonging”

author: Anita Borch

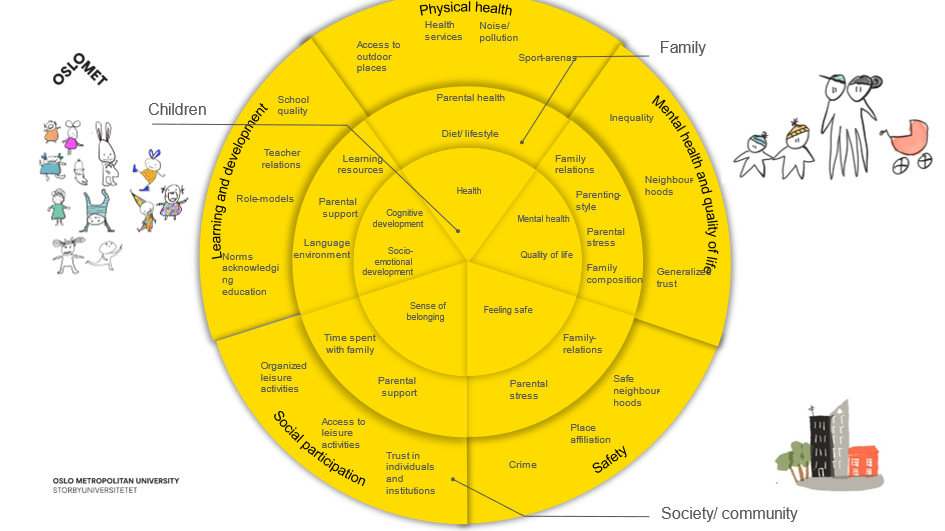

In social theory, the term “belonging” refers to a sense of ease; of “fitting in” in our immediate social context – be it people, places, or materials. For most of us belonging is positive, providing us with a sense of confidence and trust in the world, triggering us to believe in ourselves and our ability to create a life worth living. It may also have the opposite effect, connecting us to wrong places and people like criminal gangs. At a societal level, belonging is a double-edged phenomenon, leading to healthier and higher educated populations, lower rates of unemployment and robust economies. At the same time, it may split people into “in groups” or “out groups” and cause conflicts and economic recessions. Not belonging is usually associated with marginalization, social exclusion and lower levels of social welfare, but can also motivate us to turn negative spirals into positive and thereby increase social mobility. Overall, belonging and not belonging refer to complex human experiences in power to influence individuals and societies and drivers of social stabilization and change.

But one thing is how terms are understood in theory. Another cup of tea is how the term is used in practice. From a previous review, I have learned that the term “belonging” often lacks definition and that its meanings tend to overlap those of familiar terms like “social participation” and “social inclusion”. However, when I studied the use of these terms myself, I observed some differences that are worth reflecting upon.

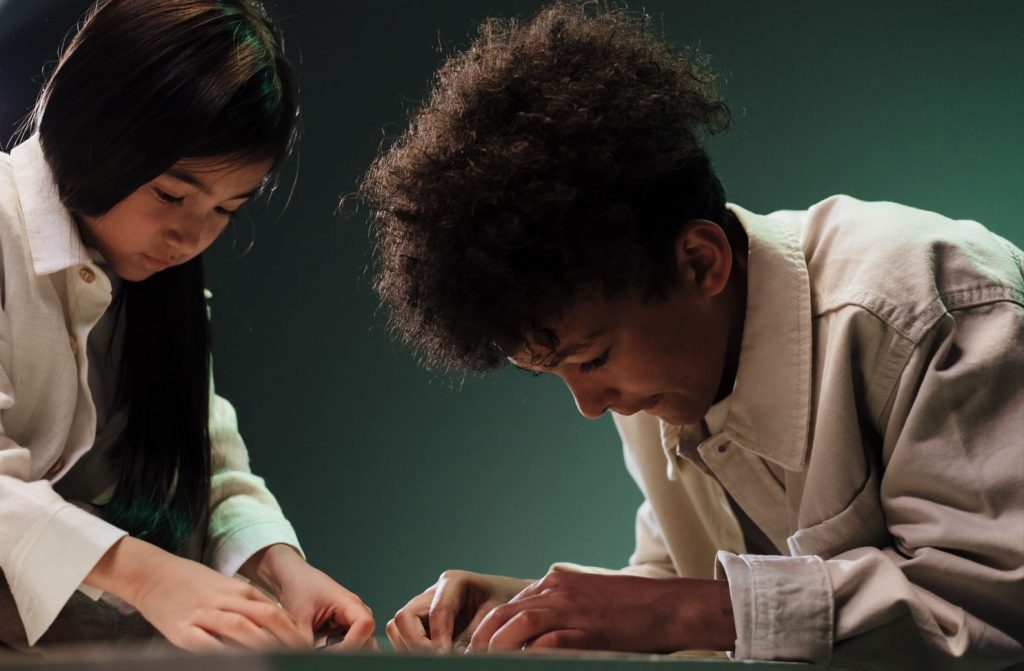

First of all, the study indicates that “belonging” is the preferred term used in studies of immigrant children’s connections. This preference seems, to some extent, to have replaced the preference for the term “social integration”, which was more frequently used in studies of immigrant children’s connections in the 1990s. Moreover, and more importantly, the preference for the term “belonging” contrast with the result of studies on the connections of the majority of children, in which “social participation” is the preferred term.

As a researcher studying children’s belonging, I feel some ambivalence regarding this latter result. Since belonging basically refers to an emotion whereas participation is often connected to an activity like sports or some kinds of decision making, it cannot be ruled out that I, by using the term belonging, implicitly and highly unintentionally suggest that immigrant children generally show less agency and, hence, that they are more passive than majority children. If so, I happen to promote a view on immigrant children that I strongly oppose. In line with other researchers studying children’s belonging, I see all children as actively involved in the process of creating belonging and not belonging. Belonging and not belonging is not one-way but mutual processes between immigrant children and their social surroundings. Not to be misunderstood, I need to make the dynamic aspect of belonging and not belonging very explicit in further work.

Whereas “belonging” and “social participation” often refer to something children feel or do, the term “social inclusion” is more frequently used to describe settings. For example, a school, a sports club, or a park in the city are typically regarded as “inclusive” if they are easily accessible for all children. The underlying assumption underpinning this view seems to be that if settings are inclusive enough, children will be included. If not, they will be excluded. The agency of the social inclusion is thereby not assigned to the children who are or should be included, but to the settings – or, more precisely, the adults responsible for creating these settings. The lack of agency and responsibility of children may explain why “social inclusion” seems to be the preferred term in studies of children with disabilities, who, in general, tend to be assigned less agency and responsibilities than other children in society at large.

Do we here see the contours of a hierarchy, in which the term “social participating” signals children with a high degree of agency and the term “social inclusion” signals children with a low degree of agency, and in which “belonging” is placed somewhere in the middle, signaling less agency than “social participation” but more than “social inclusion”? If so, the use of terms in highly cited literature on immigrant children’s connections implicitly suggests that immigrant children can be ascribed less agency than majority children, but more than children with disabilities.

The reflections made in this blog are based on observations made in a study that has recently been reported in the paper “Immigrant Children’s Connections to People and the World Around Them: A Critical Discourse Review of Academic Literature” (Borch, 2022). As mentioned, previous research has concluded that the use of terms addressing children’s connection tends to overlap, which suggests that it does not matter what kind of terms we are using. At first sight, this suggestion seems reasonable considering that terms get most of their meaning from contexts (cf. Wittgenstein). However, if we take a closer look and compare how different terms are used in practice, implicit messages may be revealed and other conclusions may be drawn. Overall, the study has shown that the terms used in studies of children’s connections can be highly political in the sense of signalling who have agency and who should be given responsibility or not. Indeed, belonging is an emotion with the power of changing children and societies. So too is how we are using terms in research and policy.