This text is authored by Kjersti Lassen, senior advisor at Consumption Research Norway, OsloMet, and was first published at OsloMet’s webpage (in Norwegian).

Researchers have studied a somewhat overlooked aspect of our household chores: digital housekeeping.

Every now and then, we might experience our Wi-Fi signal dropping, having to set up a gaming account for the kids, or managing photo storage on our phones.

Digital housekeeping

In all of these examples, we are engaging in digital housekeeping, which is somewhat overlooked in statistics on household chores.

“Everyone engages in digital housekeeping in one form or another. It can be anything from managing photo storage to programming a smart home,” says researcher Helene Teigen from SIFO, OsloMet.

She has studied the digital housekeeping done in smart and connected homes.

“Smart homes can be both practical and fun, but they can also lead to frustration and anger,” she says.

In many households, there is one partner—usually the man— who has introduced the technology, while the rest of the household members must learn to live with the gadgets that are more or less bestowed upon them. What is it like to live with technology that we haven’t chosen ourselves?

Fun and Practical

A smart home has appliances that can connect to the internet and be controlled via apps or voice. For example, light bulbs, door locks, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners. Some smart homes also have a voice-controlled smart assistant, such as Google Home or Alexa. Data from the Consumer Council from 2019 shows that one in five consumers has three or more connected products at home. Moreover, recent numbers from Statistics Norway show an increase the use of connected products. For example, the share of those who have used an internet-connected solution for energy management in the home in the last three months has risen from eight percent in 2020 to 28 percent in 2024. Households with smart kitchen appliances and white goods have increased from 17 to 23 percent in the same period.

Residents of a smart home can regulate lights and heating using an app or their voice, or play music without having to press any buttons. At best, it makes the experience of everyday life more seamless and pleasant.

“Many find having these gadgets to be positive for the household. They think it’s practical and fun,” says Teigen.

Digital Housework in Smart Homes

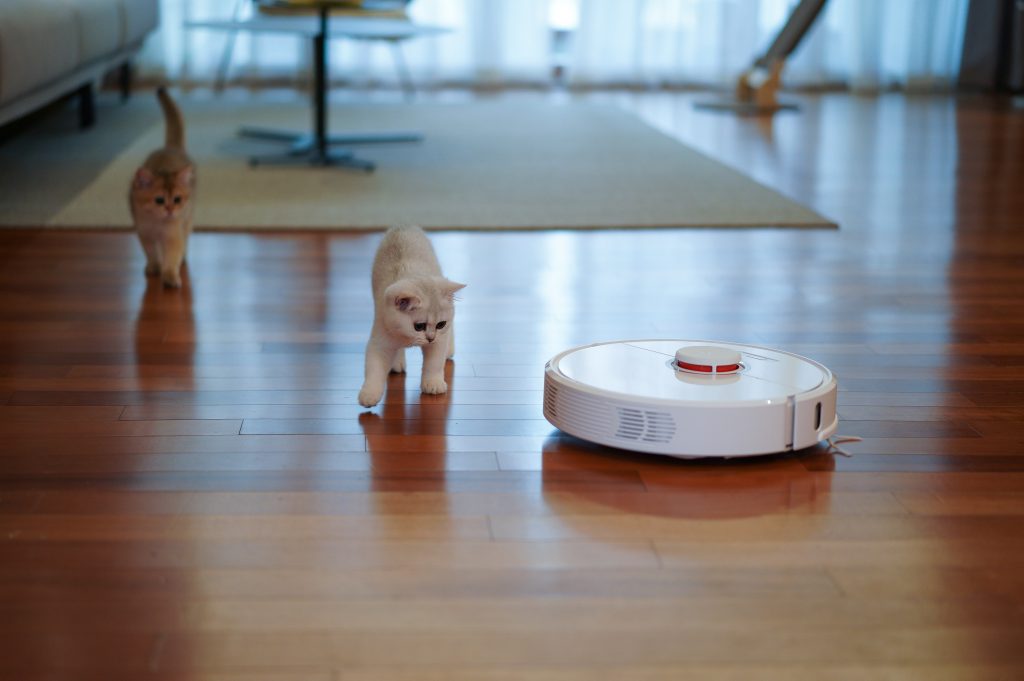

In smart homes, there is naturally more work related to digital housekeeping than in other homes. A robot vacuum can save you a few hours of work, but you can expect a bit more digital housework than from a regular vacuum.

“Digital housekeeping involves everything from doing research before purchasing, setting up the gadget to make it work as it should, and repairing or fixing any issues along the way,” Teigen explains.

All homes in the study had at least three devices connected to the internet and included various people—young and old, families and singles. Some of the informants are older individuals who received smart technology as gifts from adult children. Teigen has focused primarily on the part of the household that did not bring technology into the home but still has to live with it.

She is particularly interested in the relationship between people and technology, addressing vulnerability and uneven power dynamics.

The research shows that the use of technology can lead to an imbalance of power in the homebecause the person who don’t have control over what gadgets exist in the home, how they work, or what kind of data they collect, could be vulnerable to malfunctioning technology and to the privacy issues that they bring.

Left in the Dark

Everyone living in a smart home has to do maintenance and minor repairs along the way, and it is common and accepted to have small issues as part of the technology. These minor tasks were actually not recognized as housework at all, neither among the informants themselves nor their partners.

“The informants in the study did not see themselves as vulnerable. They do what they have to do in order to get the gadget to work the way they need it to, but they are not very interested in learning more about the technology beyond that,” says Teigen.

Nevertheless, it can be frustrating not to get the technology to work as it should.

For example, the smart assistant may misunderstand what you say because it is programmed for the partner, so you have to talk to it several times.

One informant was left sitting in the dark until her husband came home because the assistant failed to turn on the light she requested.

‘We Need Light’

Smart technology can also lead to discussions in the home. One partner—usually the man—brings the technology into the home and takes primary responsibility for it. Is it housework, or is it a hobby?

“It’s mostly men who deal with this. The men see it as their housework and believe they contribute to the household, with justifications like, ‘We need light,'” Teigen explains.

“It’s also a way to show care for the family,” she adds.

“They often take into account their partner’s or children’s needs and wishes when purchasing technology, for example, by keeping physical light switches in addition to app and voice control if a partner wants that.”

Hobby or Housework?

“Women see it more as the man’s hobby. Some of them feel the men should contribute more to more traditional household chores, especially those women who are less interested in the technology.”

Data from Statistics Norway shows that women still do more traditional housework than men. Perhaps the balance would be better if digital housework were included in the statistics?

Reference

Helene Fiane Teigen: Troubleshooting the connected home: Exploring the perspectives of non-initiators (journals.sagepub.com). Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 2024

The study is part of the research project RELINK – Relinking the weak link. Building resilient digital households through interdisciplinary and multilevel exploration and intervention. The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway.