To belong or not belong in political discourse

A while ago, an intense debate flared up between some of Sweden’s leading newspaper columnists. One of them started it all by questioning recurring statements about how children, in the wake of the ongoing inflation with increasing grocery costs as one of the outcomes, show up hungry to school after the weekends because underprivileged parents can´t afford to put enough food on the table. The columnist, also a well-known author, argued that even on a low budget it is perfectly possible – and even a parental responsibility – to prepare meals that are both cheap, nourishing, and filling. Therefore, according to the column, it is misleading to talk about these children’s predicament in terms of hunger per se [1]. The reactions were loud, upset, and immediate. The columnist was accused of stigmatizing poor parents as less knowledgeable and of displaying ‘stone cold moralism’ [2] by questioning if poor families in Sweden are really that poor, but also received some support from other columnists who saw many valid points in her arguments.

All in all, the debate boiled down to whether or not there are parents in Sweden who are so poor that they can’t afford to feed their children lentils and oatmeal, or if it in fact is an issue of parental inabilities in other respects. With a few exceptions, however[3], the arguments seldom addressed the fact that some Swedish kids, apparently, do not seem to get their basic needs fulfilled. We know from qualitative studies (see e.g. Ridge 2002; Fernqvist 2013) that children in poor households often take social responsibilities towards their parents and understate their needs in order to be less of a burden in financial terms, and it is therefore not unlikely that some children for this reason might eat less at home. An awareness of these kinds of strategies makes a discussion about how much a bag of rice costs and how long it lasts (which was also pedagogically presented to the readers in the column that started the debate) redundant as child poverty in welfare states is less a question of acute starvation and more about the complexities associated with being poor in a well-off context. This, and other nuances, was however rather absent in the recent debate, and now, a few weeks on, the issue seems to be off the agenda altogether.

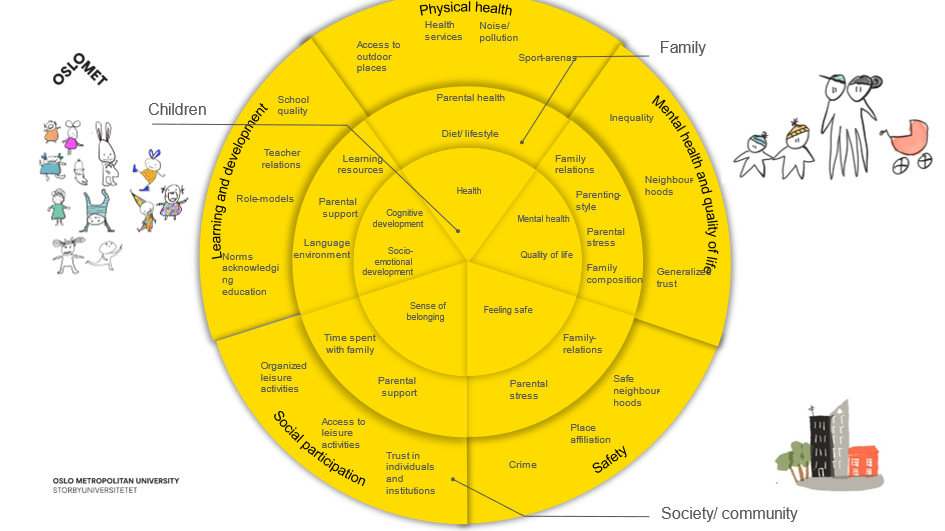

The issue of child poverty has, at times, received some attention in media and the political debate in Sweden during the last decades. Save the Children Sweden publishes a bi-annual report on the prevalence of the problem and we therefore know that around 196 000 Swedish children live in households that can be defined as poor (Salonen, 2021). Statistics from the Swedish Enforcement Agency show that the number of children who are evicted yearly is slowly increasing[4]. Nevertheless, discussions following e.g. Save the Children’s reports are often tainted with skepticism; is it possible to talk about poverty in a well-off country like Sweden? Isn’t it more a question of socioeconomic inequalities? Peer pressure in terms of consumption, where today’s children are spoiled rather than poor? As in the recent debate, it often seems to end up in a tug-of-war between morally laden opinions (often from opposite sides of the party-political spectrum) but poverty in general, and child poverty in particular, does not have a given place in media or political discourse. This may have something to do with a) that children’s everyday lives and the strategies they use to handle difficulties are less interesting on a whole, and b) a lack of consensus about how poverty in a welfare state in fact is experienced.

Poverty has historically been classified as either absolute, where ”the minimum sum on which physical efficiency could be maintained” (Rowntree 1946:102), or relative, where affected individuals lack ” the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or are at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies in which they belong” (Townsend 1979: 31). Is it, then, possible to talk about poverty in an overall prosperous welfare state like Sweden, where children are unlikely to starve but rather run the risk of being excluded among their peers due to material and social inequalities? Should we instead discuss it in terms of the right to consumption, and how this right is linked to different preconditions? Based on this vagueness, is it even possible to talk about welfare state poverty as a social problem?

Knowledge about how poor families manage everyday life has been obtained from several studies over the past decades (e.g. Harju, 2008; Fernqvist, 2013; Hjorth, 2019; Andersson Bruck, 2020), providing evidence that suggests that this issue should be getting more political attention, even in countries like Sweden. In the public debate, however, child poverty and its impact on children’s material and social conditions seem to be of less relevance. For example, the issue was virtually non-existent in the political campaigns leading up to the general election in 2022. Related issues such as e.g. segregation, increasing gang violence, and housing problems are slightly more visible, but there seems to be a reluctance to address persisting problems such as financial inequalities and child poverty. In this process, I would argue that the experiences of children and families living in poverty in Sweden – and how poverty in the Swedish welfare state should be tackled more systematically – remain rather invisible in political discourse. The occasional heated debate between prominent columnists does not change this in any substantial way.

Author bio

Stina Fernqvist is an associate professor at the Department of Social Work at Uppsala University. Her research deals mainly with different aspects of economic hardship among children and families and institutional interactions in the context of the late modern welfare state. Stina holds a PhD in sociology.

References

Andersson Bruck, K. (2020). Child poverty in rich contexts: The example of Sweden. Global Studies of Childhood, 10(2), 95–105

Fernqvist, S. (2013). En erfarenhet rikare? [Rich in experience?] Uppsala: Uppsala university.

Harju, A. (2008). Barns vardag med knapp ekonomi. En studie om barns erfarenheter och strategier [Every day life with economic hardship. A study of children’s experiences and strategies]. Växjö: Växjö University Press

Hjort, T. (2019). Vad får en soffa kosta? [How much may a sofa cost?] In T. Hjort, K. Hollertz, H. Johansson, M. Knutagård, & R. Minas (Eds.), Det yttersta skyddsnätet [The last safety net] (pp. 153–178). Studentlitteratur

Ridge, T. (2002). Childhood poverty and social exclusion. From a child´s perspective. Bristol: The Policy Press B.

Rowntree, Seebohm (1946). Poverty and progress : a second social survey of York. London : Longmans, Green

Salonen, T. (2021). Barnfattigdom i Sverige: Årsrapport 2021. Stockholm: Rädda barnen [Save the children]

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom : a survey of household resources and standards of living. Berkeley: University of California Press

[1] https://kronofogden.se/om-kronofogden/nyheter-och-press/pressmeddelanden/2022-02-23-antalet-barn-som-berors-av-vrakning-fortsatter-att-oka

[2] E.g. in a column by Johanna Frändén in the social democratic evening paper Aftonbladet: https://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/kolumnister/a/Kn1l6o/franden-fattigdom-ar-problemet-inte-lena-anderssons-asikter

[3] https://www.svd.se/a/Q7OlRV/hungrar-barnen-ar-det-foraldrarnas-fel-inte-ulf-kristerssons

[4] https://www.aftonbladet.se/kultur/a/gEjwmA/eric-rosen-om-lena-andersson-och-hungriga-barn