How can smart home devices affect belonging at home?

Belonging is often described as a feeling of being at home. In this blog post, I will explore this by looking at how smart home devices may affect this feeling among people who are not particularly invested in them. These are people who either live with someone who wanted the smart devices or have received them as a gift from other family members, but who express low interest in and/or low confidence with dealing with such devices beyond daily use. Drawing upon an ongoing study of everyday life with smart home technologies, I refer to these people as non-experts and will discuss how their troubleshooting routines reveal dynamics that may affect their sense of belonging at home.

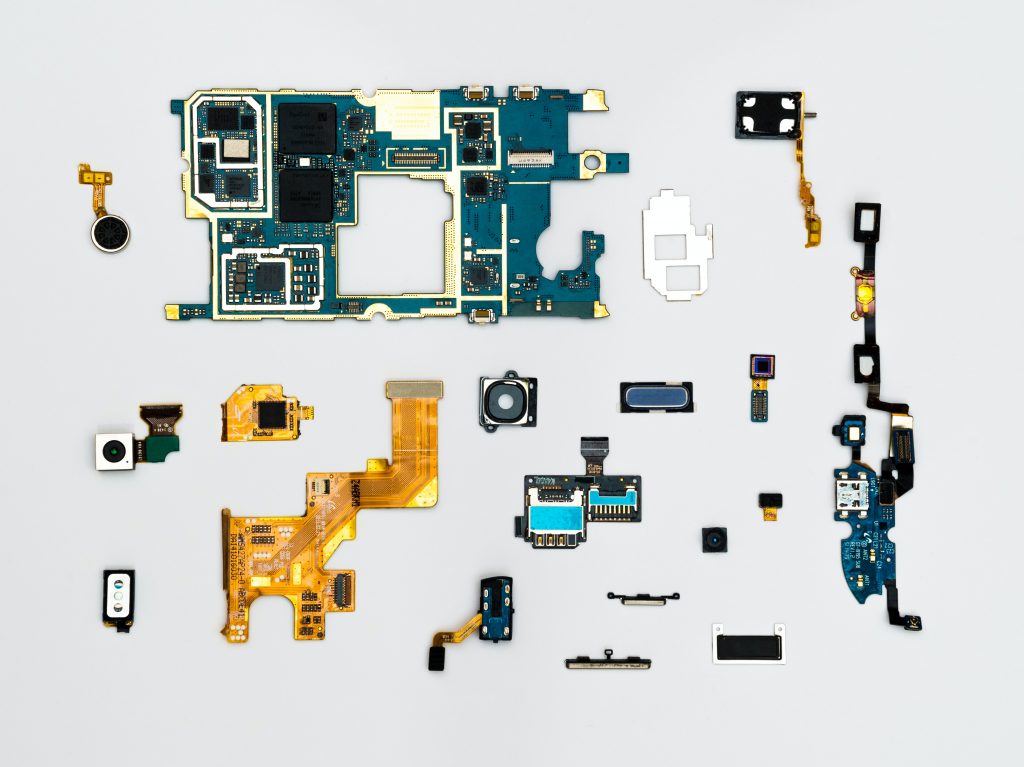

Smart home devices refer to household appliances that can be connected to the Internet and communicate with other devices. Such as light bulbs, vacuums, digital assistants, speakers, and so on.

Digital housekeeping

Digital technologies such as smart home devices require effort from people to manage and repair. In literature, this domestic tech work is often referred to as ‘digital housekeeping’, and the responsibility is often afforded to one person, most often a male dubbed the ‘expert’. However, technological malfunctions and disruptions are normal when living with technology and affect everyone who uses them – not just the one responsible for managing them. Trentmann (2009) further argued that disruptions could illuminate dynamics of everyday life that are otherwise difficult to spot. As such, I am using technological malfunctions as an entry point to look at how smart home devices may affect the sense of belonging of those who are not considered experts.

Troubleshooting routines

The non-experts encounter various issues with the technology on an almost daily basis, ranging from temporary loss of Wi-Fi or miscommunication with voice-controlled assistants to more complex interoperability issues. When facing such problems, non-experts had to pause what they were about to do and engage in troubleshooting. I have identified three main steps of non-experts’ troubleshooting routines, which are to identify the issue and a possible cause, performing by engaging with the technology to fix the issue, and if they are not able to do so; delegate the problem-fixing to someone else – either the expert in their family, a network of extended family and friends, or external actors such as the companies behind the products, internet providers and so on.

Material, relational, and cultural aspects of troubleshooting

The non-experts’ troubleshooting routines are shaped by material, relational and cultural dimensions.

The material dimension such as the design and infrastructure of smart home devices affect what and how non-experts can engage with them, often providing an easy interface for use but a complicated system for troubleshooting. Smart home devices have a substantial “black box” operating system, which the non-experts do not engage with and don’t fully understand. This makes it more difficult to locate a cause for the issues and disruption and thus to find a solution. The devices further receive software updates from time to time, changing them, which may generate new and unfamiliar issues. This does not allow the non-experts to gain expertise through routinization.

However, non-experts do have some knowledge and skills to draw upon when facing issues, and they can be creative and resourceful when dealing with smart home devices. They are not completely helpless, but when facing issues they cannot solve themselves, they are dependent on experts to help. This dependency brings me over to the relational dimension.

The work that non-experts engage in, is affected by the household composition and its social dynamics, making out a relational dimension. Giving someone a smart device means also providing them with digital housekeeping tasks. None of the non-experts had brought devices into their home themselves. It was either done by their partners or received as gifts. Moreover, tech enthusiasts tend to create a more complex home network with more devices from different providers, do-it-yourself, and customized solutions. This makes it more difficult for other household members who do not have the skills and knowledge about these solutions and how they work. The result may be that it makes them more dependent on the experts as they may encounter more issues that they cannot fix themselves. As such, being the tech expert at home comes with some power in terms of household control because they control the technology, while the non-expert may lose some of that control as household activities are entangled with smart home devices they are not fully mastering.

This could also result in one person, the expert, spending more time on domestic tech work, leaving more of the traditional housekeeping work to the remaining household members.

However, it is important to mention that this is a negotiation process, where the non-experts have the opportunity to affect what kind and how many devices they receive through for instance communication, expectations, and acceptance. In technology forums, for instance, is often talked about a “Wife Acceptance Factor”, which is the perception of what the tech enthusiasts’ partners will accept of technology.

A cultural dimension also plays a role in terms of gendered ideas about technology and home. Among the five non-experts in this study, there were four women, and two, including one man, belonged to a senior age group. As previously mentioned, these were the study participants that expressed low confidence with or low interest in the smart home devices. Although it could be coincidental, the fact that they represent women and seniors fits well into the gendered and generational perceptions of the home and technology. For instance, the home has traditionally been a female domain, while technology has been a masculine one. The technology industry is still predominantly masculine, making many of the technological devices less suited for women, and the elderly often find it more difficult to keep up with technological development than their younger counterparts. This is reflected in the uptake of smart home technologies, which is higher with young men than women and older age groups. Moreover, the tech expert is in literature most often identified as a man, which can be argued to enroll men into housekeeping through domestic tech work – but can also lead to a reinforcement of traditional gender roles as the remaining household members are left with more of the traditional domestic work.

Belonging

As the non-experts’ daily doings often are entangled with or sometimes dependent on smart home devices, the technology malfunctions quite often, and the non-experts are not always to solve the issues themselves, they may at times be in a position where they are not able to perform their daily doings as they are used to or wish to do. This creates a dependency on the experts around them to perform simple everyday tasks, preventing them from asserting full agency at home. It may lead to a lack of familiarization, confidence, and ownership of the technology – which may affect their sense of belonging at home. As such, it is important to look at consumption and materials when exploring belonging.

The concept of belonging relates to a sense of place, identity, and relationships. It holds both positive associations, such as warmth, and security, and negative associations, like exclusion. Belonging is also relational and political, constructing boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’. With this in mind, the analysis of the non-experts’ troubleshooting routines shows how this may affect their sense of belonging by excluding them from exerting full agency within their home, and further constructing boundaries between the non-experts and their expert counterparts. Those boundaries further represent asymmetric power relations in terms of agency and domestic control, and follow generational and gendered lines.

Author’s bio

Helene Fiane Teigen is a Ph.D candidate at Oslo Metropolitan University, at Consumption Research Norway (SIFO) institute. In her doctoral project, she explores the role of smart home technologies in people’s daily lives. Her research interests include the materiality of technology, technology and social relations, privacy, gender, digital competencies, inequalities, and digital marketing.

Further read

Interested in learning more about digital vulnerabilities in smart homes? Check out the Relink project and their blog.

References

Nagel, C. (2011). Chapter 7. Belonging. In V. J. Del Casino Jr, M. E. Thomas, P. Cloke, & R. Panelli (Eds.), A Companion to Social Geography (pp. 108–124).

Trentmann F. (2009). Disruption is normal. Blackouts, breakdowns and the elasticity of everyday life. In: Shove E, Trentmann F, and Wilk R (eds) Time, Consumption and Everyday Life. Practice, Materiality and Culture. Oxford ; New York: Berg, pp. 67–84.