By Carlos Y. Flores (text and photos)

In January 2023, the whole Riverine Rights research team met in New Zealand for a workshop and trip along the Whanganui River. Read Carlos Flores’ report of the experience here.

In January 2023 the second in-person meeting of the whole Riverine Rights project’s team led by Axel Borchgrevink and John Andrew McNeish, took place in New Zealand. The Whanganui, together with the Ganges in India and the Atrato in Colombia, are rivers which were granted legal personhood in recent years, and the reinforcement, applicability, and sociocultural effects of these legal innovations are at the centre of the Riverine Rights research project. Other members of the team who took part in the meetings and activities in New Zealand were researchers Liz Macpherson, Miriama Cribb, Catalina Vallejo, Bibhu Prasad Nayak, and Rahul Ranjan. Rachel Sieder and Gro Ween from the project’s advisory board also took part, as did water rights researcher Cristy Clark and visual anthropologist Carlos Flores.

The New Zealand Government’s recognition in 2017 of the Whanganui River as a living entity with legal personhood is a clear example of the long-run disputes over territory, land and natural resources that have marked the history of Aotearoa New Zealand. Sovereignty and the relationships between human and non-human entities – particularly, in the Māori worldview, between tangata (people) and whenua (territory)- have been at the heart of numerous negotiations. In 1840 the Treaty of Waitangi, now recognized as the nation’s founding document, was drawn up between more than 500 Māori chiefs and the British Crown. The Māori chiefs understood the treaty meant that their rights to land and natural resources would be protected by the Crown, which would extend them protection, while the colonial legal interpretation was that the Maori had in fact ceded their sovereignty. The treaty was contested since its inception, eventually contributing to wars between 1845 and 1872 and continuing through to the Treaty of Waitangi settlements which started in the early 1990s. During the second half of the 19th century Māori generally lost control of much of the land they had owned, sometimes through legitimate sale, but often by way of unfair land-deals, settlers occupying land that had not been sold, or through outright confiscations. Although in the late nineteenth century, the government largely ignored the treaty, by the mid twentieth century Māori increasingly sought to use it as a platform for claiming additional rights to sovereignty and to reclaim lost land and greater control over territory. In 1975 the New Zealand Parliament passed the Treaty of Waitangi Act, establishing the Waitangi Tribunal as a permanent commission of inquiry tasked with interpreting the treaty, researching breaches of the treaty by the Crown or its agents, and suggesting means of redress. It is against this backdrop that the significance of the Whanganui river’s legal recognition as a person should be understood.

The first research workshop of the Riverine Rights. Exploring the currents and consequences of legal innovations on the rights of rivers, took place at the Faculty of Law of the University of Canterbury, in Christchurch, on Monday 16th. Members of the project, advisors, and Māori and non-Māori academics discussed the experiences of river rights not only in India, Colombia, and New Zealand (the countries that the Riverine Rights project focuses on), but also heard presentations about the Waikato/Waipa River (also in New Zealand), water rights in Australia, and relations between states, indigenous peoples and territories in Ecuador, Guatemala, and Norway. A range of positions were in evidence and participants discussed the desirability or not of extending a Western concept of human rights to rivers, as well as the role of academia in these political and environmental shifts. For much of Māori cosmogony, the whenua (land, rivers, seas, forest, air and ultimately the whole universe) are already living entities at the same level as humans: the granting of legal personhood to the Whanganui river was described by many researchers as simply a means to an end in a long struggle for territorial control.

On Tuesday 17th of January, the team travelled from Christchurch to Taupō and from there south around lake Rotoaira, near where the Whanganui river starts. They were received by Hayden Turoa, a local hapū (subtribe) representative, who first welcomed the team in Māori and then in English and invited us to get our feet into the water and greet the river. At the head of the river, we saw installations that divert the water of the river to the Te Whaiau Dam, a hydroelectric facility owned by Genesis energy company who are in an ongoing dispute with the local Māori. The team visited the company next day, but didn´t talk with any of its representatives. Hayden later took us to a nearby site Te Pōrere, where some of the battles of Tītokowaru’s War (1868-1869) took place between the Ngāti Ruanui and Ngāruahine Māori tribes and the New Zealand Government. He gave the team a comprehensive talk about this confrontation and the symbolic and political importance that this site has for the Māori people.

On Thursday 19th, the team left the Tongariro region for Whakahoro, whre we would start the river journey by water. We stayed in a European farm-style station at the edge of the national park. The man in charge of the Blue Duck farm, who was of European descent (Pākehā), had an informal chat with us to talk about the environmental degradation of the area which he saw as due to intensive farming. Together with other local Pākehā, he was reforesting some of the surrounding hills with the government’s help. Such regeneration has created new economic possibilities for people in the area by attracting tourists and hunters among others. However, how best to tackle the physical degradation of the river and its surroundings is still under discussion between government, private landowners, and Māori representatives.

The next day the team took a jetboat and went downstream the river to Bridge to Nowhere, where we were received by local Māori guide Hayden Potaka and his children. The two-hour canoe journey downstream began towards Tīeke Kāinga, the site of a river marae (Māori collective house) and a hut owned by the department of conservation. As it is customary, the team was welcomed in Tīeke by local people in Māori oratory and traditional songs in an exchange ceremony known as põwhiri. There are over 700 marae all over New Zealand, sacred sites with great cultural meaning and multiple social purposes which are usually linked to iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes). The walls of the collective bedroom where the team stayed were adorned with photographs of local Māori ancestors, underlying the importance the marae hold for cultural identity. The person in charge, Woody Firmin, later gave us an explanation of the history and significance of the people and place.

On Saturday 21st, members of the team guided by Hayden paddled 21.5 km from Tīeke to Pipiriki, crossing some rapids and fluvial landscapes with different levels of deforestation. The destruction of hills with dynamite during the 19th Century is still visible; this was carried out for the colonising forces to widen the river for the navigation of steamboats upstream, demonstrating the historically contested nature of the territory.

Once in Pipiriki, the team took the canoes out of the water and went to stay at Rānana Marae.

As with the first marae, we were greeted with a põwhiri ceremony. From the pictures displayed in the marae, the influence of the Catholic Church through missionary work in former decades was clear. After dinner Whanganui iwi leader, Gerrard Albert, gave an extremely comprehensive explanation of the historical conflicts and negotiations between the Māori and the Pākehā, underlining the national and international political alliances that had been forged to advance Māori rights within the Crown (government) legal system.

The following day, the group continued its research journey towards Te Ao Hou Marae, located in the city of Whanganui, where the river encounters the sea. After the traditional welcoming põwhiri and dinner, there was a brief exchange with Geoff Hipango, the man in charge of the marae, which, as all marae, is used for communal gatherings like births, funerals, and other important social events.

The next day members of the team were able to present the overall research project to local scholars and activists and other people from around Whanganui in a meeting held at the place.

During our time in Whanganui, the team had the opportunity to get to know the history, geography and context of this river city and river people. We also visited the Whanganui Regional Museum, founded in 1892 and famed for its Taonga Māori Collection, where precious objects of Māori and Pākehā identity and history are displayed. Later, there was the visit to the Ngā Tāngata Tiaki’s offices (the entity in charge of the river’s governance model under the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act. It gave the Whanganui River the status of a legal person in 2017 and the first appointees to be the human face of the Settlement were inaugurated. The team was received by the second appointments made in 2021, Keria Ponga, Crown Appointee, Turama Hawira, Iwi Appointee, and some advisers appointed by other local authorities to Te Kōpuka, like Wiari Rauhina who administer the Te Korotete Fund. We were given a rich explanation of how the iwi and hapū of the river have an inalienable interconnection with, and responsibility for, Te Awa Tupua -a living and indivisible entity- and its health and wellbeing.

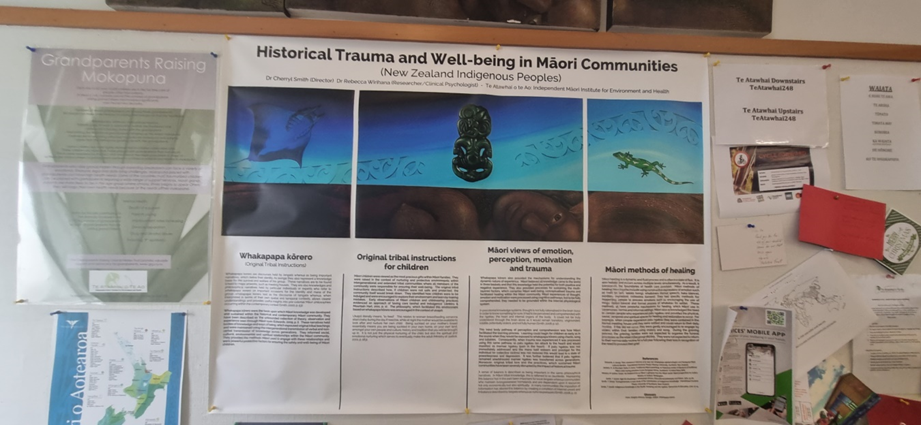

Finally, the team had a fulfilling exchange with researchers based at the internationally recognised research centre Te Atawhai o Te Ao, the Independent Māori Institute for Environment and Health which grew out of the Kaupapa Māori schooling movement and the revival of Māori language in the late 1980s. One of the supporters of the Riverine Rights team in New Zealand and a current member of the institute, Miriama Cribb, introduced the team to Dr Rāwiri Tinirau, its current Director, Professor Graham Smith, and other collaborators of the centre. During the presentation, we learnt that Kaupapa Māori research is one that values Māori ways of doing things, following underlying principles such as self-determination, cultural aspiration, culturally preferred pedagogy, collective philosophy, and addressing historical trauma. As was explained, before 1980, there was little interest by Māori people to professionalize at high level education, but because of long-term strategies and support from social scientists and activists, some of them still working in the institute, today there are more than 500 Māori with PhDs and interest in studying is much higher than before. This, undoubtedly, strengthens their demands for rights within ongoing negotiations with the Crown.

At the end of the trip, in an unexpected turn of events, some members of the Riverine Rights Project team were unable to leave New Zealand to travel home when Auckland (where the main international airport is located) was hit by its worst storm in history. On 27th January the city received the equivalent of three months of rain. Streets and houses were inundated, four people died, all international flights were cancelled, and the event made the international news. This unprecedented disaster was clearly connected to climate change and underlines the importance of better understanding the relationships between human activity and nature, or between human and non-human beings. As we learnt on this research trip, in Māori cosmogony, the whenua (territory and the entire universe) must be respected and cared for as our equals, as living entities.

Postscript by Axel Borchgrevink: An even worse cyclone – Gabrielle – hit New Zealand on February 13th. At the time that this news item is published, neither death toll nor damages are clear. But it is being characterized as the worst natural disaster New Zealand has experienced. This only underlines the message with which Carlos Flores ended his report.