Sarah Marchiset, Mélanie Vivier

Once a week at SIFO, a common lunch is organised during which a researcher presents a paper while his/her colleagues are eating.

An overview of the “food rhythm” in Norway:

Living in Oslo for a month, Sarah and Mélanie tried to adapt to – and first, to understand – the way people who compose their environment eat in their everyday life. Mostly at work, where they try to blend into the landscape, and to copy the way the colleagues surrounding them eat and act during commensality moments.

To say it was challenging would be a bit of an exaggeration (would it?). However, it needed some adjustments…

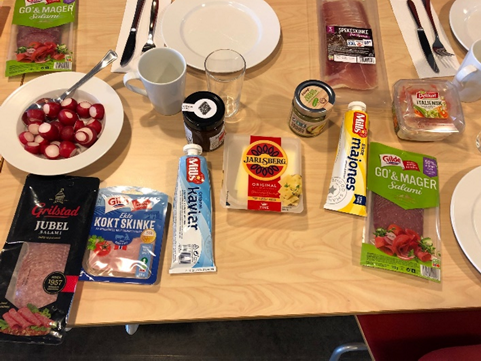

Talking about “food habits” while considering a country or a specific group of people sounds for them as a risk of culturalizing the Other, and therefore confining him/her into categories which are often more a matter of fantasy than reality as experienced by this Other. This is the reason why they choose to use this expression with precaution. Nevertheless, it is also necessary to consider that between places, spaces, people, and depending on temporalities and movements, the ways of cultivating, cooking, eating… – that is to say food practices- from garden fork to fork, can differ a lot. In Norway, it appears that the way of eating of the majority is to split the day into different food intake parts, ranging from meals to (many) snacks. At 11.30, it is lunch time. For Mélanie and Sarah, the common lunch has a taste of “brunch”. Not the proper time, nor proper components to call it a “lunch”, the way they consider it in their daily lives at home.

Pieces of cakes, chocolate spread, are dancing among bread, cheeses, including the brown one – brunost – which is sweet with caramel taste (no offense to cheese purists!) and often eaten with waffles or just bread, Norwegian kaviar, ham and other slices of dry meet and vegan options, tomatoes, cucumber, and other fresh vegetables, ready prepared salads, without forgetting the famous and delicious cinnamon rolls (sometimes revisited). Juices, coffee and tea go with the buffet.

Waffle with brown cheese tasted and approved by Sarah & Mélanie in Norway

Apart from the common ones, other lunches sound quite familiar to Mélanie. They taste, from her point of view, a little Belgian (Belgium being her “adoptive country” since a while), more like a salty snack than a meal. But of course, the question needs to be asked: what is (or is not) a meal? Hard to define, obviously embedded in subjectivities. Defining (or trying to define) a meal depends on dynamics of identifications. But it also reflects hierarchies’ relationships. Oh that! Mélanie and Sarah – with all their “Frenchness” – know a lot about it. Is it necessary to recall how political food is in all these aspects? Between (attempts to) heritage registration with Unesco, labelling, appellations, negotiations on a planetary scale in terms of imports-exports… hierarchies are also expressed in the way in which “proper food”, “eating well” or “better eating” is defined from above, just as much as what is or what is not “gastronomy”, thus reflecting power relations between majority and sociological minorities, at different scales. Food as a whole tells us a multitude of stories: those individuals who, through it, also find a way to express their subjectivity and their feelings of belonging (plural and mobile) over time, places, encounters. But food also tells us the story of places and spaces through time. Just think back on the story of sugar over time and spaces for example[1]…! And more broadly, on the story of triangular trade, colonialism, capitalism and the way it permeates foodscapes tight down to our plates, and from our fields. It tells us our story, that of a common humanity, which can share, unite around it, but which also seeks distinction, domination, negotiating and recomposing permanently. Food reflects a system that, while being normative, is in constant motion. It also reflects hierarchical relations in our globalized societies crossed by movements, circulations, of human beings, certainly, but also of ideas, products, recipes, know-how, standards and values…

From this (necessary) digression, let’s get back to our Norwegian lunch. Maybe more than the contents of buffets, meals, brunches (or whatever), Sarah and Mélanie felt more disturbed by the moment of the day for it. And even more by the moments for the different snacks and meals. Once a week, it is collective cake time at 2p.m – and they learnt from a reliable source that, apart from this time of collective culinary sharing, the offices around them are overflowing with small culinary moments where everyone nibbles and enjoys little snacks. This may explain the relative frugality of lunches! Unless this is another subjective interpretation…! But here again the pen digresses. Concerning the weekly cake time, one person is in charge of bringing a cake, whether “homemade” or purchased. What a great opportunity of delight for one’s taste buds, while (re)discovering sweets and showcasing the culinary know-how of colleagues or surrounding pastry chefs. It is also during these kind of foodie moments that belongings, exoticism and ethnicity can find an expression. Let’s just have a quick look on what Mélanie and Sarah decided to bring on their last day at SIFO, for the common cake-time: a “gâteau au yaourt” (“yogurt cake”), which they described as a “typical” French pastry (but let’s decentre and de-ethnocentrize for a moment: to what extent is it really or only a “French culinary specialty”?), tasty and simple, that many children prepare with their parents (but let’s be honest: their culinary talents didn’t allow them to bake a “Paris-Brest” anyway). This “gâteau au yaourt” has thus donned the costume of a warm thank you for the welcome, while grasping a certain form of “Frenchness” embodied at this moment by the two young women.

After a day of work (most people leave the office between 4p.m and 5p.m), Sarah and Mélanie, wandering in Oslo, generally enjoyed the city by drinking a coffee or a beer as a convivial way of ending the day before having dinner. But they were always dubious. 5p.m: time for another snack, aperitif or dinner? Fortunately, their colleagues enlightened them on this subject. As early as 4p.m / 5p.m, Clara says it is considered as “normal” (no matter what “normal” is) to have dinner, even though apparently most people have dinner around 6p.m. Later, it is time again for a little snack. Eating time habits that can change from one person to another, as well as from one place or space to another, and depending on temporalities. Eating habits (in times and content of food intake) that some people coming from elsewhere can take and make their own, sometimes to the point of preferring them even when returning to their so-called “home” country. Such is the case of Clara, a young PhD student from Germany who has been living in Oslo for several years and who confides to the two French women the way in which she has embedded new eating habits leading her to noticeably live the “old” ones as strangely foreign. Thanks to her, Mélanie and Sarah have had the opportunity to understand at least a few pieces of the Norwegian foodscape. Among them, the “Friday tacos” which seems to be popular among a large part of the Oslo inhabitants, as a way of sharing a dinner that can easily satisfy all eaters thanks to the flexibility and the autonomy that it implies regarding food stuffs composing this meal: ready-made ingredients and/or homemade ones; based on fish, meat, vegetarian or vegan; at home or in a restaurant…

Talking again about eating time habits, Virginie says, on the contrary, that even after several decades living in Oslo, she has never managed to make Norwegian meal times her own. Her “Frenchness” – or maybe better to say her process of humanisation / ethnicization (see Danielle Juteau on this point)[1] – probably finds an expression there, in the way in which her body cannot express the desire to eat and therefore to incorporate food at times that she does not identify as conductive to food consumption. A feeling shared by Paula, a woman from South America who works at the food bank, and whom you will meet in the next post!

[1] See L’ethnicité et ses frontières, Montréal, Presses universitaires de Montréal, 1999.

[1] See Sidney W. Mintz, Sucre blanc, misère noire : le goût et le pouvoir, Nathan, 1991