Children as experts.The Children’s Worlds Survey and its potential

Sabine Andresen and Asher Ben-Arieh

Children are experts. They have knowledge, experience and opinions, but they are often not listened to. With the help of the children’s rights approach, the scientific interest in children and their role as experts is changing. In recent years there has been a growing interest among international researchers, policy makers and professional practitioners especially in the issue of children’s subjective well-being (SWB). The relevance of this concept arises for a number of reasons. One is the recognition that the use of traditional indicators such as Gross National Product as an indicator of societal progress has limitations and needs to be augmented by an orientation toward well-being or even the happiness and satisfaction of the population or of specific groups within the population, including children (Casas, 2011). However, it is also argued that possessing knowledge about the life situation of adults is not the same as possessing sufficient knowledge about children (Ben-Arieh, 2005). The issue of children’s SWB has to be addressed within the context of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the associated challenges regarding its implementation. The CRC acknowledges the importance of taking into account children’s views in matters that affect their lives (United Nations General Assembly, 1989).

Data collection: Children in Nepal filling out the survey.

Nevertheless, while research on adults’ SWB is well established, interest in children’s SWB is more recent (Ben-Arieh, 2012). Current studies, have focused on questions such as how to define children’s SWB, how to measure it, and above all what are children’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives (see for example Dinisman, Fernandes, & Main, 2015). However, much is still yet to be known about the comparative perspective. Specifically, do children share common SWB simply because they are children or whether and how children from different parts of the world differ in their appraisals of their lives? This is fundamental knowledge in order to grasp a more complete picture of what constitutes a good childhood and how we can ensure this is available to all children.

Together with colleagues from many regions of the world and the generous support of the Jacobs Foundation in Zurich, we have succeeded in launching the first ever global study, the International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCIWeB). This study included a number of waves of a representative survey of 8-12 year old children. It is of particular importance that not only adolescents but young children from the age of eight are involved (Andresen et al. 2019). In the participating countries, children in schools are invited to participate in the study and thus their voice is captured worldwide. Anyone interested can get an insight into how the questionnaire is structured and what the results are via the website (https://isciweb.org). The project is based on the idea that one of the most important factors in assessing whether a particular environment is conducive to children attaining their best potential is the perception of their own sense of well-being. This is best done by asking children directly and by allowing them to give an assessment of their own well-being. Thus, the survey is based solely on the children’s own evaluations, perception and aspirations.

Data collection: Dr. Mekonen collecting data in Ethiopia

Furthermore, the project is a cross-national, cross-cultural and multi-linguistic survey in which a variety of countries and cultures around the world take part. Consequently it provides valuable local and comparative insights into the lives of children in a diverse range of cultural contexts and substantial new information about how children live their lives. These national and international perspectives make it possible to improve our understanding of the nature of childhood in different contexts and draw implications for local, national and international policy. Additionally, the

use of newly developed quantitative assessment instruments for children, which cover relevant life domains, offers important understanding of methodological issues in comparative research with children.

The project began in 2009 when a group of researchers, mainly from the International Society for Child Indicators (ISCI) with the support of UNICEF, acknowledged the potential need for an international survey of children’s subjective well-being. This resulted in a draft questionnaire which was then tested in two sets of small-scale pilots in the summer and autumn of 2010 and in the first half of 2011 in a total of nine countries (Brazil, England, Germany, Honduras, Israel, Romania, South Africa, Spain and Turkey), each followed by review and an evaluation of the questionnaire.

This learning led to the design of separate versions for children aged 8, 10 and 12. Up to now more than 200,000 children participated in the various waves of the project from more almost 50 countries. This shows that children want to be asked, they want to be heard and they have something to say.

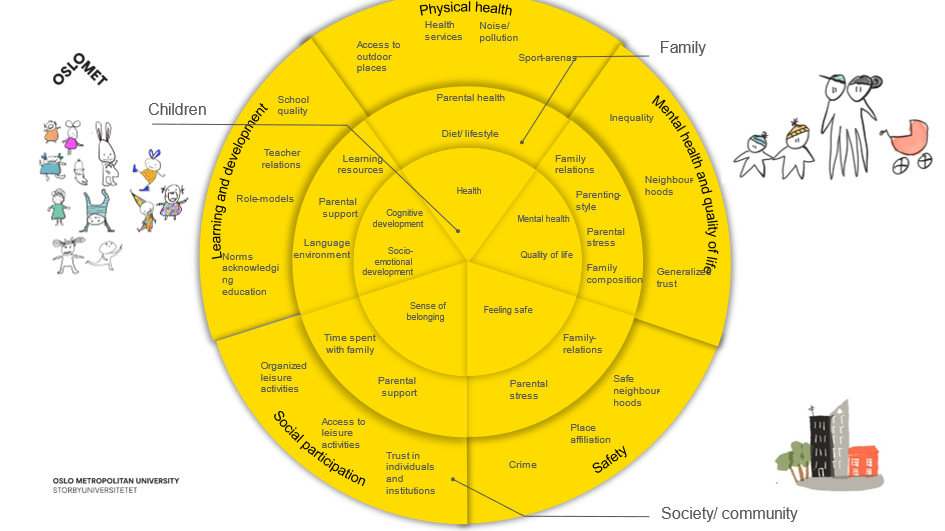

Children’s SWB is a complex and multidimensional concept, and consists of several aspects. The Children’s Worlds survey provides rich data on numerous domains in children’s lives. We thus gain important knowledge about relationships in families, with friends, learn something about how safe children feel in schools or neighborhoods and what strongly or less strongly influences their SWB. These international data offer countless opportunities to compare children’s lives within and between different countries. There are also opportunities in all countries to discuss findings with children themselves. This is an important next step in enabling more participation. Finally, we are especially proud that many researchers are using the study findings to inform governments and practitioners on how to improve the situation of children.

Acknowledgements

The Children’s Worlds: International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB) is supported by the Jacobs Foundation.

References

- Andresen, S., Bradshaw, J. & Kosher, H. (2019). Young Children’s Perceptions of their Lives and Well-Being. Child Indicators Research 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9551-6

- Ben-Arieh, A. (2005). Where are the children? Children’s role in measuring and monitoring their well-being. Social Indicators Research, 74(3), 573–596.

- Ben-Arieh, A. (2012). How do we measure and monitor the “state of our children”? Revisiting the topic in honour of Sheila B. Kamerman. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 569–575.

- Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4, 555–575.

- Dinisman, T., Fernandes, L., & Main, G. (2015). Findings from the first wave of the ISCWeB project: International perspectives on child subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research, 8(1), 1–4.

- United Nations General Assembly (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. New York: Author. Retrieved from: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm.